Should the Gay Muslim Man Forgive His Homophobic Immigrant Parents?

Probably! But my answer might've been different when I was younger — or before I left America to travel the world.

For the audio version of this article, read by the author, go here.

Last month, the New York Times published an essay, “I Let My Parents Down to Set Myself Free” by Tarek Ziad, about a young gay Muslim man and his difficult relationship with his very traditional immigrant parents.

The man’s family immigrates from Morocco to Florida, opens a small business, and experiences what sounds like fairly vicious racism and Islamophobia. The future writer acts out, and the parents discipline him according to the mores of their homeland — that is, very strictly.

After a series of massive sacrifices by his parents, Ziad ends up in college, where he begins “the process of finding myself, unburdened by the expectations of their traditionalist worldview.”

That is, he cuts his parents off.

Later, when Ziad hears his parents are desperate to make contact with him, he unblocks his number.

“My eyes scanning the floor, I called [my mother] back,” Ziad writes. “I heard the relief and happiness in her ‘Hello?’ I told her I’d finished my junior year. I was studying acting and writing solo shows. And, oh yeah, I was having sex with men.”

Now his parents block him.

“It’s a tough lesson,” he writes, “accepting that my happiness could be linked to my parents’ misery. But I had to shatter their idea of me as simply the troublesome son with authority issues.”

Later, his parents reach out again, asking if they can attend his graduation. But he insists that his college boyfriend be there, so they reluctantly decline.

After that, they still regularly invite him home for holidays, but now he always declines because they still can’t accept his “queerness.”

“Even though I crave the love of a family dinner, I can’t head home knowing not all of me is invited,” Ziad writes. “I must refuse to splinter my ego, even as it deprives the part of me that misses his parents. And I do.”

Instead, he cultivates “new memories, a new relationship to faith, a new life. My life. People who love me, make me laugh, whom I love” — a chosen family.

Obviously, it’s none of my business how this guy lives his life, and I’m generally reluctant to judge other people’s choices anyway, especially when it comes to something like being gay.

On the other hand, when you write about your life-choices online, you’re asking people to judge them — by definition. That’s the whole point of writing a personal essay, right?

Problem is, even hearing this story from within his own self-serving framing, my judgment is that this guy sounds like kind of a selfish jerk.

He cuts his parents out of his life without explanation, and when they reach out to him, one of his first comments is to announce he’s having sex with men? Despite their coming from an incredibly traditional background?

Dude’s apparently never heard of the concept of “diplomacy.”

Which, again — fine. It really is none of my business.

But I also think he’s making a huge mistake — if only because it sounds like his parents really are trying to meet him halfway.

Okay, yes, his parents won’t accept “all” of him. But he’s clearly not willing to accept all of them either: he’s asking them to splinter their egos by foregoing their traditional Muslim beliefs.

Funny thing, though. As immature as this Ziad guy seems, he sounds vaguely familiar. When I was in my twenties, I said very similar things.

My parents were also socially conservative — devoutly Catholic — and they had an extremely difficult time accepting that I’m gay. When I came out, my parents both said horrible things to me too.

Honestly, even after all these years, I’ve never been able to forget them.

When Ziad’s parents reach out to him, and he responds by saying he’s having sex with men, he is obviously trying to hurt them — a fact that even the author acknowledges.

Back then, I wanted to hurt my parents too. After all, they hurt me first. And they were the adults — I was just a kid.

Then two things happened.

First, I grew older, and I realized that life was far more complicated than I had thought.

To my great surprise, my parents changed; slowly but surely, they evolved. By the time my dad died at age ninety-four, my devoutly Catholic father was proudly introducing me and Michael all around his retirement community: “This is my son Brent and his husband Michael.”

I also realized that even adults still make mistakes — big ones. Over the years, I’ve said my own share of horrible things to people that I suspect they can’t forget either, even if I really wish they would.

That’s why I can’t even judge Ziad that harshly. He’s still in his twenties. Forgive me if I sound condescending, but he has absolutely no idea how in need of grace and forgiveness he will soon be.

Most of us are pretty good at demanding dignity for ourselves, but we’re less good at granting it to others, especially when it comes at a cost to ourselves.

As for the chosen family, I have one of those too, and I treasure it.

But here’s another thing you don’t realize in your twenties: sometimes members of your chosen family start families of their own, and their priorities shift. And sometimes people just move on.

Meanwhile, your parents will always be your parents.

There are absolutely things that parents can do where the kid is fully within their rights to cut them out of their life forever.

And I also recognize that sometimes giving yourself space is an important part of a process that can lead to reconciliation. You prune a tree, and it grows back stronger than before.

But the older I get, the higher I think the bar for “family estrangement” should be.

That’s because I’ve also discovered how incredibly short and precious life is.

A few years after my disastrous coming out, I learned my mom was sick with Early Onset Alzheimer’s Disease. Before long, she didn’t recognize anyone, not even her husband.

Except she always recognized me, right up to the very end. How incredible is it that I was there to be recognized?

Now I’m almost the age that she was then, and in the last three weeks, I’ve learned that three of my closest friends have some form of cancer. Back in March, another friend learned he had cancer too — the husband of one of those just diagnosed.

At this point in my life, I couldn’t give the slightest fuck if I have to splinter myself a bit to have more time with my dead parents or any of my close friends.

Only someone in their twenties could possibly be foolish enough to decline a dinner you yearn to attend because of a difference of opinion. Go, damn it! Sort all that other stuff out later.

The second thing that happened that shifted my view of family? I left America to travel the world as a digital nomad — and I saw that outside of the United States, people have a completely different relationship with their relatives.

I quickly realized what a massive outlier America is, prioritizing things like “self-expression” and “personal happiness” over things like “duty” and “familial obligation.”

I’d always heard that America was “individualist,” but I had no idea how true this was — nor how extreme the individualism.

In America, the self is really important, and our personal wants and needs usually come first, and this is rarely even questioned. In other countries, it’s often the other way around — and this is also rarely questioned.

Ziad doesn’t seem to have realized it yet, but this is one of the things his immigrant parents gave him: an identity as an American. He’s deeply absorbed and is now displaying America’s strong sense of individualism.

But I’m not sure this gift was such a good one. And I’m not sure rejecting his parents has made him “free.”

Back in my twenties, I was certain that “family” was a dying institution — oppressive and dysfunctional.

And some of the time, it is — especially for LGBTQ people, women, and anyone who feels “different.”

But “family” is one of the things that age has made me realize is very complicated.

The more I travel the world, the more it seems to me that people are happier when they’re part of a vast, complicated network of relatives — the more extended the family, the better. The ties that bind also provide much-needed support — not to mention a sense of purpose and belonging.

And the longer I’m away from America, the more Americans seem to me to be miserable — so often isolated and lonely, paranoid and angry.

I think American values — and our troubled relationship with the concept of “family” — are a big part of the reason why.

Anyway, should Tarek Ziad forgive his homophobic immigrant parents, at least if they really are willing to meet him halfway?

It’s obviously not up to me. But if it was me, I sure as hell would.

See also…

The Incredible Beauty of Unlikely Friendships

The "Chosen Family" Isn't All It's Cracked Up to Be

My Father Just Died. Here's the Eulogy I Gave at His Funeral

Christmas Dinner at JoAnn's — for More Than Fifty Years

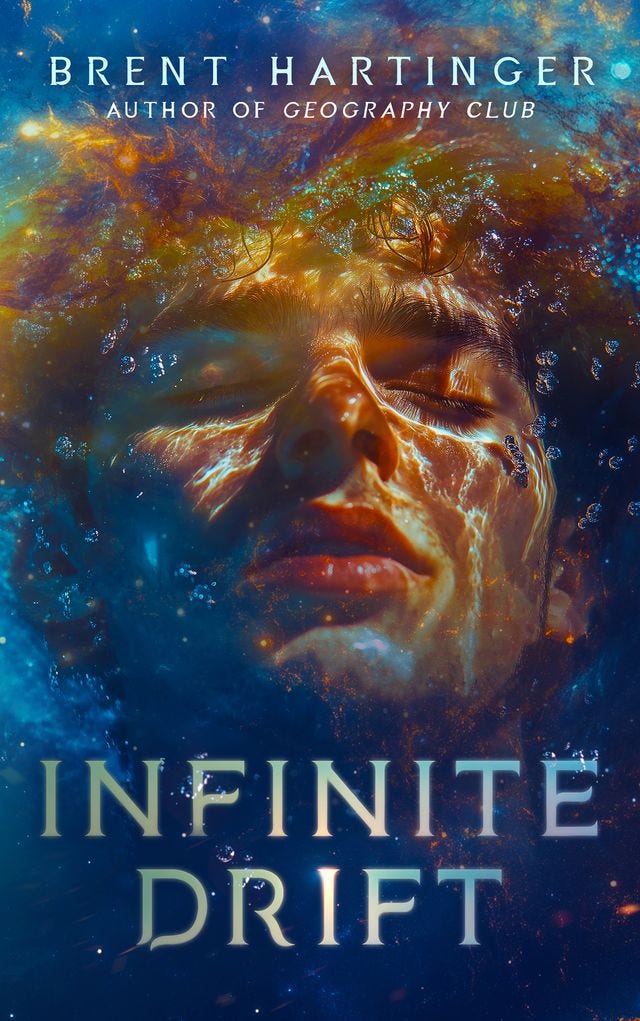

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author. Check out my new newsletter about my books and movies at www.BrentHartinger.com. And preorder my latest book, below.

Here’s my answer: No, he does not need to forgive his parents now or ever. My question is why is it that the LGBTQ family member is always expected to forgive in these situations, yet the conservative, often religious members of the family never need to do anything? They can continue with their epithets, crude jokes, hurtful comments, and overall disrespect for us and we should say or do nothing. However, if we dare to bring up something important in our lives, we’re accused of “throwing it in their faces” or “ramming it down their throats.” Yes, this has happened to me even after repeated attempts over forty plus years to reach out. But not just me, also my husband and many of our friends. So the author may be doing himself a favor and freeing up decades of unnecessary family drama so he can live his life guilt-free.

The good news is people have capacity to change, parents and kids. Freshman year in college I was extremely homophobic. Had a roommate I belatedly found out was gay and behaved deplorably. I was from a small conservative town, conservative family, conservative boys boarding school. But by senior year in college I’d come full circle (and this was long before anything called “LGBTQ”). I would hate to think my freshman year friends think I’m still the same person I was then, because I’m not.