The "Chosen Family" Isn't All It's Cracked Up to Be

The concept of the "family of choice" hasn't lived up to the hype. Leaving America and traveling the world helped me understand why.

I was in my twenties the first time I heard the concept of the “chosen family,” and it’s hard to overstate how much it resonated with me.

Yes! I thought. Forget my biological family, I want to spend my life around people who love and accept me for who I am — the “family” I choose!

Then again, I’m gay, and I’d come from a conservative Catholic family with parents who had an extremely difficult time with my being gay. Plus, this was the 80s and early 90s, at the height of the AIDS/HIV epidemic, and I’d seen so many people with the disease cruelly judged or rejected by families who claimed to love them.

It didn’t help that this was also the height of the “pro-family” conservative movement — and that term, “pro-family,” had been coined specifically to reject LGBTQ people and our rights.

In other words, at that point in my life, almost every time I heard the word “family,” it was literally defined as an institution that excluded me.

In a way, me and my gay friends had no choice but to create our own families — build our own “28 Barbary Lanes” from the Tales of the City books. Some, like the drag families featured in the landmark documentary Paris is Burning, even featured literal parental figures — drag “mothers.”

And trust me, those chosen families saved a lot of lives.

But thirty years later, the landscape of the chosen family looks different to me. For one thing, most biological families are far more accepting of their LGBTQ members now — at least in America and Western Europe.

This has mirrored my own family, which went on to become very gay-supportive. Not long ago, pre-Covid, my elderly father laid down the law with the other folks at his retirement home: he refused to sit with anyone who didn’t support same-sex marriage.

But the concept of the chosen family itself also never really lived up to its hype.

The idea definitely went big-time. Friends and Sex and the City defined the late 90s zeitgeist, not Leave it to Beaver or Little House on the Prairie.

In fact, culturally speaking, I’d say we LGBTQ folks completely won the “family” argument, and the prevailing message in mainstream American entertainment is now way beyond even that of Friends and Sex and the City. The new message is fairly consistent: the cool people leave their families and go off to have exciting (if neurotic) single lives in the city, while the boring, stupid people get married and have kids.

Basically, the traditional family is oppressive and dysfunctional — an outdated paradigm that should be mocked and rejected. In its place, we should all now assemble our own families of choice.

But even though we won the argument, I’m not sure we won the war. Without the bonds of culture and tradition, how strong are chosen families anyway? Do they really last?

I think about my own chosen family from back in my twenties. At the time, I thought we’d be tight forever.

But things changed. Some members of my circle — both gay and straight — had kids and their children became their top priority. In other cases, people changed cities or took in aging parents. We all moved on with our lives — and hey, my husband Michael and I eventually left America to travel the world as digital nomads.

I’m still friends with most of my chosen family of way back when — in some cases, very good friends. And as world travelers, Michael and I have since made another solid circle of close nomad friends.

But I see now that the role these people play in my life isn’t really the same as family.

As for the larger LGBTQ community, people don’t seem to be any less lonely and isolated than before we started boldly forging all these chosen families. In fact, there’s some evidence that “coming out” makes a gay person more depressed, not less.

In fact, all Americans seem more lonely and anxious than ever.

And, sure, there are a lot of obvious reasons for America’s current epidemic of anxiety and alienation — economic pressures, cynical TV executives and political operatives, and (especially, IMHO) social media, which is literally designed to turn people into frustrated addicts.

But I’m increasingly convinced the deconstruction of “family” is also at least part of the reason why America is so messed up.

It’s a very strange thing, being old enough to see an obscure fringe belief you once completely identified with and totally championed go on to become a dominant cultural belief — and suddenly you’re able to see that, along with its essential truths, the concept also contains some real flaws and limitations.

Sure, the concept of the chosen family has been great for the privileged class, and the young and attractive — people who have the money or connections to shield themselves from the brutalities of life. Now they have even more resources to focus on themselves and their own personal happiness.

But what about the elderly? The disabled and the neurodiverse? Addicts? The misfits and oddballs? And children? When chosen families go mainstream, and everyone is picking and choosing their “family” members, what happens to the folks who take more than they give? Are they simply on their own — the responsibility of an impersonal government?

Let me be very, very clear about one thing: I think for a very long time, traditional families in America completely failed their LGBTQ members. They failed women too. Many families are still failing these groups. In traditional countries and cultures, the problem is far, far worse than in America.

It also must be said: despite having been treated so poorly by “family,” many LGBTQ people — and women — do the lion’s share of caring for elderly parents. Ironic much?

I also hope it goes without saying that I acknowledge that some families and family members are so toxic and abusive that they should be completely rejected.

(At the same time, it feels to me like some people are now defining “toxicity” and “abuse” so broadly that the terms sometimes feel meaningless — and some of these folks have ended up pathologizing frustrating-but-normal human interaction. But your mileage may vary.)

Where has my reassessment of “family” come from anyway?

More than anything, it was that decision Michael and I made to leave America. Before I knew it, I was confronted by something I truly hadn’t expected — namely, when it comes to “family,” America is a massive outlier compared with the rest of the world. Outside of the United States, most people have a completely different relationship with their relatives.

They also seem, well, happier. There's always the danger that I'm seeing the rest of the world through rose-colored glasses. And families in the rest of the world are definitely changing too — becoming less traditional, less tightly woven over the decades.

But not nearly as fast as in America, where massive, sweeping changes have happened almost overnight.

The rest of the world also really does seem far less anxious and neurotic than my home country.

As a result, I’ve come to think that maybe “family” isn’t the oppressive, horrible, irredeemable, dysfunctional institution I once thought.

Or, rather, yes, maybe it is, some of the time — especially for LGBTQ people, women, and, frankly, anyone who feels “different.”

But there are also benefits to the family that I didn’t appreciate back in my twenties — benefits that simply aren’t replicated by a chosen family.

Living for months at a time in countries like Mexico, Thailand, Vietnam, Turkey, Romania, and Czechia, I’ve heard many local friends talk about their families — that vast, complicated network of relatives who are an integral part of their daily lives.

Everyone complains about the obligations and responsibilities they feel toward this tangle of people, and I’ve definitely heard people express frustration and exasperation over what seem like genuine slights and real injustices.

But I’ve heard so many good things too — so much actual love. In the best case scenario, there’s always someone looking out for you. And no family member is ever left behind.

And since they’re talking about extended families, the messages they receive are often surprisingly diverse. After all, even more conservative families tend to have an “eccentric” aunt or a free-thinking uncle.

For better and for worse, the bonds of culture and tradition really are strong. Amid these interconnected family relationships, people gain a real sense of identity and a feeling of rootedness — even if, yeah, they probably lose some personal freedom. Life is definitely less about self-expression.

Which leads me to what may be the real problem with American families: unlike the rest of the world, American families underwent a massive social change in the 1950s — from a rich, complicated “extended” family model, to a smaller “nuclear” one.

One father, one mother, and their kids — preferably living in the suburbs.

It makes sense this change happened in America, because Americans see themselves, first and foremost, as individuals. I couldn’t see this when I lived in America, but now that I’ve left, this sense of American individuality feels so overwhelming that it’s almost hard to put it into words.

And the nuclear family did give many Americans a new kind of freedom — and a lot more opportunities, at least for white men.

It was also great for the American economy; it’s a big part of the reason why America is a superpower right now. After all, all those individual white families had to have their own house — and a lot of their kids got to have their own bedroom too. And they had to fill all those rooms with stuff.

Corporations loved the nuclear family because it was an opportunity to sell more things to Americans and make even more money.

But in the end, the nuclear family ended up being absolutely terrible for American society. In a way, it was the worst of both worlds — creating an emotionally stifling environment while depriving people of any sense of identity or culture. I think the nuclear family was worse for women too, isolating them from what had previously been, yes, a blatantly unfair social order, but also a rich social network of female interaction and respect.

In what universe does it make sense for a couple — and, often, mostly the mother — to raise their newborns almost entirely alone?

Maybe this is what LGBTQ people like myself were really rebelling against back in the 1980s: not family per se, but the nuclear one.

But in a way, the chosen family wasn't so much a rebellion as it was the natural next step, after nuclear families, in an increasingly individualistic and self-centered America. And, of course, it was a way for corporations to make even more money. Now every single person needed to fill their whole house or apartment with things.

Like the nuclear family, chosen families also came with huge limitations.

Look, the extended family model is far from perfect. And even now, some form of chosen family still has a place in the world.

But things aren’t black-and-white. I see now that traditional family networks evolved the way they did for a reason.

So what’s the solution? How do we make American families functional again?

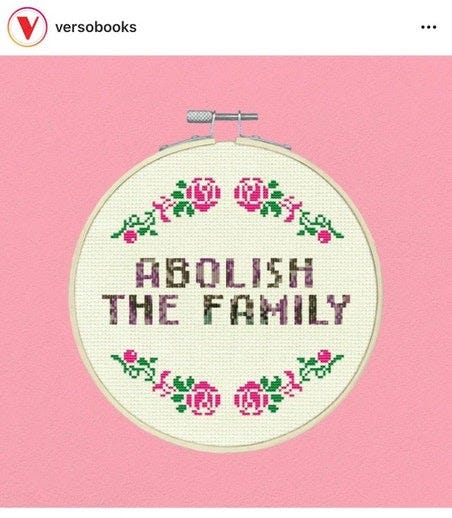

First, I think progressives need to stop with the wholesale demonization of all things family-related. In Hollywood, it may be emotionally satisfying for writers who feel misunderstood by their own families to ridicule them, but it’s simplistic and patronizing. And when radical leftists say really stupid, politically disastrous things like “Abolish the family!” more moderate progressives need to be very clear and say, “That’s a kind of bigotry, and these people don’t speak for me.”

The rich, complicated social networks I’ve witnessed in other countries seem more interesting to me now than yet more trite smugness about how horrible and oppressive “family” is.

As for conservatives, well, they need to start actually supporting families — financially, I mean, with policies like paid parental leave, and affordable child care, housing, and health care.

They can also start to see that egalitarianism is good for everyone. Let’s face it: conservatives’ bigoted, exclusionary “pro-family” rhetoric is a big part of the reason America is now in the mess it’s in.

The children’s author Judy Blume once wrote a book titled Places I Never Meant to Be. That title describes the way I feel right now. How in the world did I — someone who couldn’t wait to replace his biological family with his newly chosen one — become this person who is now saying, Hold on now! Let’s not throw the baby out with the bathwater.

But here I am. Life surprises you. I’ve surprised myself.

In the end, the chosen family didn’t solve all of society’s problems, and it even created new ones. Who knew?

But Americans still have a choice. We can now pick and choose from the best of both models.

It would be nice if this time we finally got the answer right.

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author. Check out my new newsletter about my books and movies at www.BrentHartinger.com.

Great article, thanks for sharing! I think some import context is the decline of other social institutions -- unions, churches, societies/fraternities, and now for some, workplaces. We have fewer places where we are consistently exposed to the same people, and fewer institutions providing the social scaffolding that families can also provide. This might contribute to loneliness, and make "chosen families" harder to achieve.

Well said and definitely food for thought. I have a foot in both worlds, and was a part of the nuclear family. My husband and self, two sons. My husband has passed after nearly 40byrs of marriage. My parents are gone. One son is gone. My sisters live 2.5 hours away. My chosen family/ friends have helped me to survive. To open up to trusting others, and learning how to live "solo"