Las Fallas in Valencia, Spain, is the Coolest Festival You've (Probably) Never Heard of

It's like Burning Man times three hundred.

For the audio version of this article, read by the author, go here.

Las Fallas, which takes place in Valencia from March 15th to March 19th, is Spain’s second largest festival, but I’d never even heard of it.

This is even more surprising given that, like Burning Man in America, the festival culminates dramatically in fire. Except, unlike Burning Man which only burns a single effigy, Las Fallas involves the burning of hundreds of “fallas” — that is, different artistic installations made of wood, Styrofoam, and papier mâché.

And “la Cremà,” which is what these final conflagrations are called, is just one small part of this amazing festival.

Brent and I recently spent six weeks in Valencia, but not because of Las Fallas. We didn’t even realize it was happening until after we’d made our arrangements.

But by the time we arrived in mid-February, we’d seen photos of la Cremà, and we were both very intrigued.

By March first, the locals were already getting in the mood, setting off firecrackers at all hours of the day and marching through the streets playing music. Valencia is the birthplace of paella, and residents also began cooking great, bubbling pans of their most famous dish on sidewalks and in squares all over the city.

I was determined to learn all about this upcoming festival, so I enlisted the generous help of Eline van den Heuvel, the co-owner of a local, independent tour company, Valencia Inside.

Two weeks before Las Fallas, Eline arranged for me to visit Ciutat Fallera, or Fallas City. This is a collection of old warehouses that has been converted into huge artists’ workspaces: where the various fallas artists construct their different flammable displays.

This is where I first got the sense of how seriously this city takes their festival. I have no idea how long it takes Burning Man to build their single effigy of wood every year, but I’m sure it’s nothing like what happens in Valencia.

Most neighborhoods in the city have their own “casal,” a kind of community organization. And each casal commissions their own individual falla, hiring artists who sometimes spend the entire year designing and building these temporary works of art. The largest fallas can cost up to €250,000 — or $265,000 USD — and even the smaller ones cost many thousands of dollars

This year, Valencia’s various casals unveiled almost eight hundred different fallas — every one of which was burned at the end of the festival.

At Ciutat Fallera, I was able to see artists putting the finishing touches on their works. It turns out the casals usually do two versions of their falla: the central one and also a smaller, thematically related piece for children.

No one knows exactly how this all started, but the festival dates back to the Middle Ages. It probably began as a way for carpenters to honor Saint Joseph, the patron saint of carpenters. Historians theorize they probably burned the leftover scraps of wood collected during the winter.

Before long, the carpenters and their neighbors began making figurines— called “ninots,” Valencian for “doll” — out of the scraps.

Eventually, many of the ninots became satirical, poking fun at the powerful members of Valencian society.

And over the years, they became much more ambitious — bigger, taller, and more colorful. Most now incorporate Styrofoam and papier mâché, and some tower impossibly high.

“Las Fallas is much more than just the fallas and ninots,” Eline told me. “It’s also la Crida, la Planta, the Ofrenda de Flores, and of course, the mascletà.”

I didn’t know what any of that was, but I was determined to find out.

And I did, attending as many of these events as possible.

La Crida, or the Call, was the opening night of the festival, marked by speeches and a fireworks show.

La Planta, or the Installation, was when the hundreds of fallas created for the festival were installed in the neighborhoods all across Valencia on a single night.

Ofrenda de Flores, or the Offering of the Flowers, was a procession of more than a hundred thousand men, women, and children dressed in traditional attire, carrying bouquets of flowers to Plaza de la Virgen. In the plaza, the flowers are gathered up to literally build a massive monument of the Virgin Mary.

And a mascletà turned out to be the setting off of row after row of firecrackers and other explosives hanging from strings, all of them connected by fuses. This pyrotechnics display has to be seen and heard — and felt — to be believed. And they do this every day for nearly three weeks, all over the city — supposedly, to ward off evil spirits.

Brent joined me for some of this, but to hear him tell it, I was becoming my usual, obsessive self.

Perhaps so, but there were still things I was missing. One night, I was too tired to go to the Nit del Foc, or Night of Fire, which is a fireworks display over the incredible City of Arts and Sciences.

More than that, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I was missing the most important part of Las Fallas. What in the world motivated the Valencians to put on this fantastic — and fantastically complicated — festival every year? What role did it play in Valencian society? Because this seemed like more than just another festival.

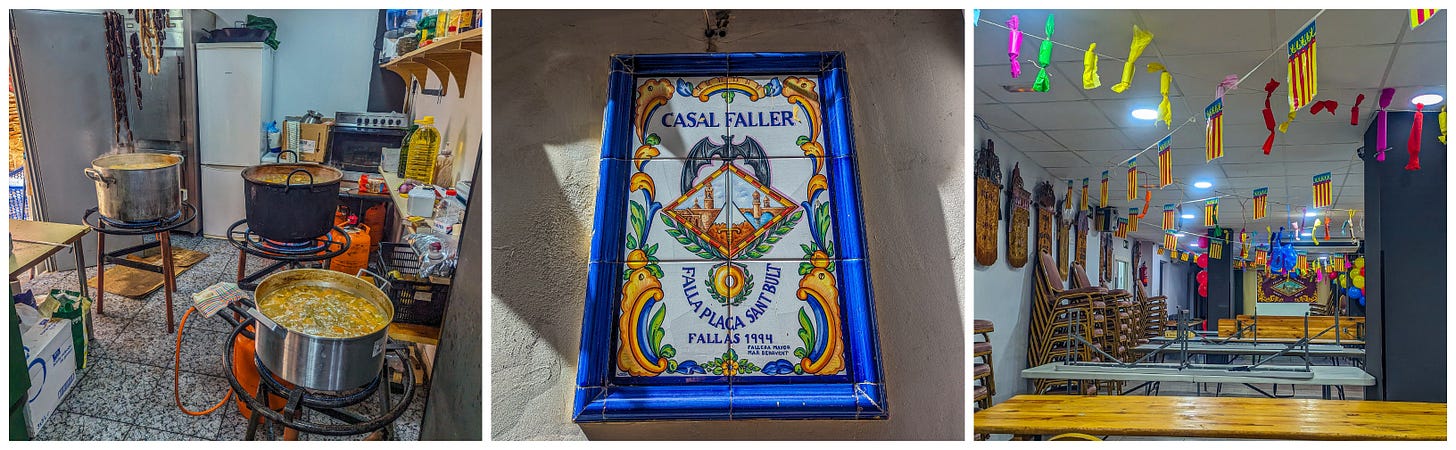

Once again, Eline came to my help, bringing me to the headquarters of one of the casals, Sant Bult, located in Old Town.

With la Cremà fast approaching, it was a busy day for the members of Sant Bult. In the nearby kitchen area, three big pots of soup bubbled away, ready to feed the casal’s 150 members when they returned from visiting a nearby casal — another important part of Las Fallas.

Amid the bustle, Eline introduced me to Marcelino Rubio Vidal, one of the officers of this 150-year-old casal.

Sant Bult’s fallas was a towering Black woman dressed all in yellow with a headdress of flowers, birds, and fruit. I was curious how the casals paid for incredible works of art like this, especially ones that would only be displayed for a handful of days.

“All year long, our casal hosts dinners and fundraisers to raise the money we need,” Marcelino said, with Eline translating. “Plus we get sponsorships from businesses.”

“So that’s the function of the casal?” I asked. “Planning the project and raising the money?”

Marcelino shook his head. “It is much more than just that. We also have presentations explaining the importance of Las Fallas to younger people. We do classes teaching about the hairstyles and the traditional clothing. And we go and meet with the other groups and spend time socializing.”

So it was about more than just the spectacle?

“I think maybe eighty percent of Valencians participate in Fallas in one way or another,” Marcelino went on. “Some join a casal. But others just participate in the ofrenda and march in the parade. Others go to the fireworks or to watch la Cremà.”

“Many others work building the fallas themselves,” Eline added. “That employs many people, as does manufacturing the firecrackers and fireworks. All of that is done here in Valencia.”

“So in a way, this binds the city together?” I suggested.

Marcelino nodded. “Exactly. I think before I was born, I was already in the Fallas.”

A short time later, Eline and Marcelino led me outside, and I immediately heard the sound of a pasodoble, the lively Spanish music used in bullfights. A small marching band of musicians was fast approaching.

A moment later, we were surrounded by music and people in traditional costumes, everyone singing and laughing.

A grandmother, mother, and granddaughter, all shimmering in colorful fallera dresses, held hands and spun around in a circle.

Nearby, a father “danced” with his infant son.

Mostly, I saw joy — so much that I found myself moved nearly to tears.

I tried to think of an American equivalent. The Elks or Rotary Club? The Superbowl? Maybe celebrations at some churches, synagogues, and mosques, but even America’s big holidays — Christmas, the Fourth of July, and Thanksgiving — paled in comparison to this.

“This is genuinely magical,” I said to Eline. I had to talk over the sound of the music.

She grinned.

So here it was: I’d finally found the point of Fallas — its meaning. The ninots and mascletas were fantastic and fun, and I was soon to be dazzled by the raging bonfires of la Cremà.

But Las Fallas is really about this community and the way the festival has bound them together for hundreds of years.

I was genuinely happy for people I was watching, as well as the city of Valencia.

But I was also a little jealous — and even a little sad — because I’ve never known anything quite like this myself.

Here are some more photos from la Cremà.

Michael Jensen is a novelist and editor. For more about Michael, visit him at MichaelJensen.com.

Two years I spent in Spain (southern) and never heard of this. Fantastic. But sad to see all that art go up in flames.

This is incredible! Thanks for sharing. I was in New Orleans for Mardi Gras earlier this year and it blew my mind - I hadn’t realized the extent of creativity and community that is deeply part of that cultural festival! But generally I agree that festivals in the US feel bland and simple. We are going to a neighborhood Memorial Day parade today and I’m going to look at it through the eyes of a wandering tourist now after reading this. Might make it more fun?