Have Tourism and Gentrification Been Good or Bad for San Miguel de Allende, Mexico?

It's complicated. But maybe not *that* complicated.

Want to start a massive online argument? Post something online about San Miguel de Allende — the colonial-era UNESCO World Heritage-listed city located in the high plains of central Mexico.

Even worse, say something about the impact of international tourism and gentrification on the town.

It seems that almost anyone who’s lived in or visited the place has a very strong opinion on the matter.

How do we know?

Oh, just a hunch — it’s certainly not from our personal experience living here for three months and posting about it online. And we’re positive this article won’t trigger that kind of reaction either.

Okay, yes — sarcasm alert. And no, we’re not trying to preemptively rebut criticism of anything we’ve written here. If someone posts their opinions online, part of the deal is that you have to be open to disagreement and even criticism.

When it comes to San Miguel de Allende, here’s the starting point, the thing that most people agree on: there’s something special about the place.

If nothing else, it’s very beautiful, especially the city center.

In fact, Travel + Leisure magazine has named San Miguel de Allende “the best travel destination in the world” three times: in 2017, 2018, and 2024.

“San Miguel is a town of 180,000 people, but it supposedly has six hundred different restaurants, not counting taco stands,” says Vail Smerlinder-Suarez, a local tour guide at Taste of San Miguel. “You could eat at a different place every night for two years.”

And everyone also agrees that the town has seen a hell of a lot of change in the last several decades, with a massive increase in regional and international tourism — and a corresponding increase in foreigners moving to the city to live, especially in the city center, which has seen major gentrification.

But here is where opinions diverge.

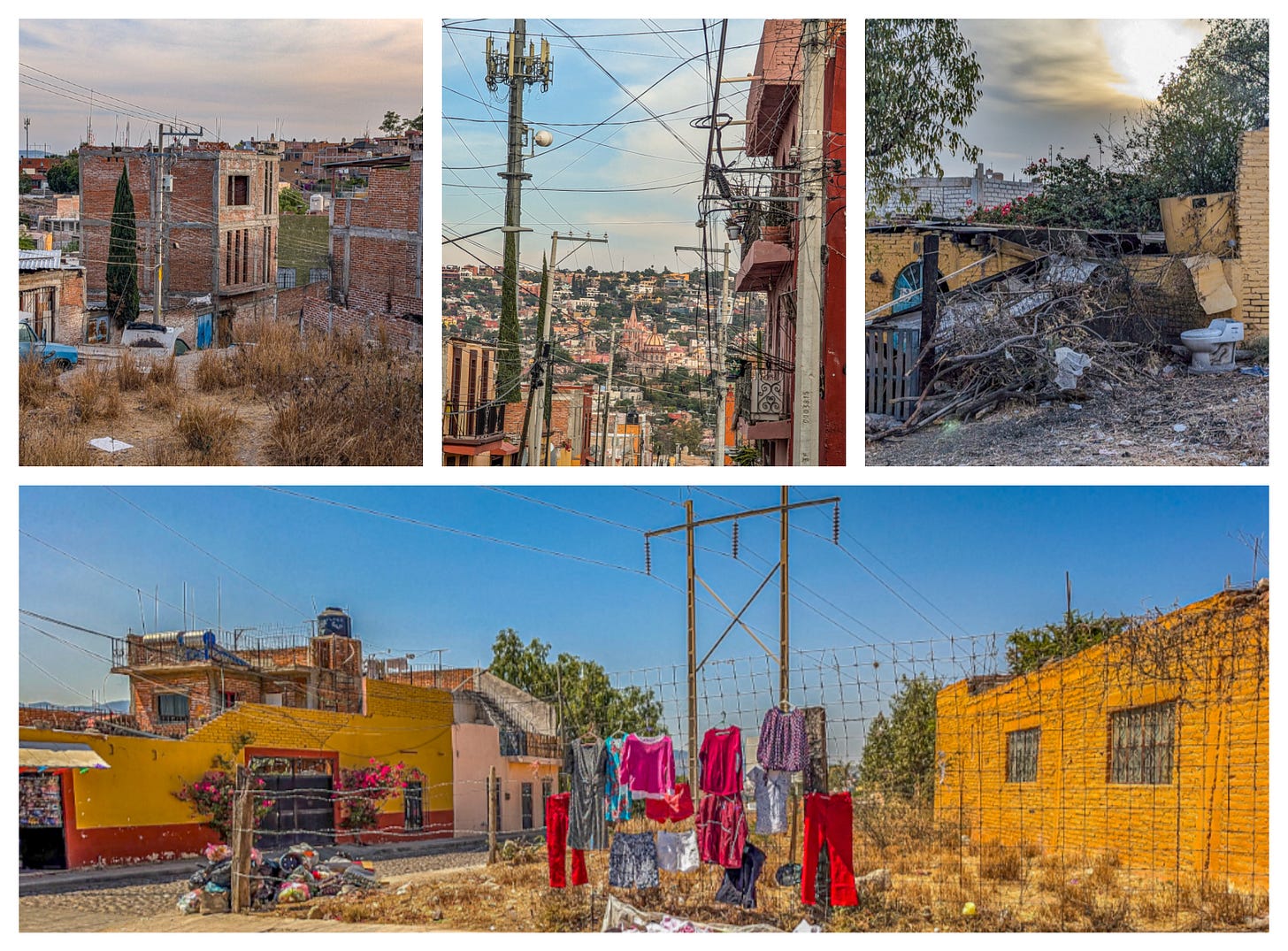

“The issue is thorny,” writes Josemaria Moreno, one local observer. “Our city, for a couple of decades now, has followed a gentrification trend like perhaps no other city in our country.” This has led to “exorbitant rents, segregation, and housing displacement of the labor force to the peripheries of town. Many of these areas lack basic services, facilities, and security.”

Smerlinder-Suarez agrees that the issue is complicated but points out, “Most of our tourists are Mexican. The gringos” — foreigners, especially Americans — “get a bad rap for gentrifying [San Miguel], but we’re kind of like the Martha’s Vineyard or the Hamptons in America: Mexican cities where many [rich] Mexican people have their summer homes, their weekend homes. Yes, there are nine thousand foreigners living here, but that’s out of a population of 180,000.”

The cost of local housing has indeed risen dramatically. In the past decade, the median home price in the central area has gone from $324,000 USD to $540,000 — prices that are ridiculously out of reach of most locals in a city where the average monthly income is $682 USD.

And the city now has at least 3,000 active Airbnb listings, further reducing the housing supply for locals.

At the same time, housing costs outside the “expensive” areas aren’t nearly as high — and wages are higher than in other parts of Mexico too. Plus, many of those Airbnbs are owned and/or operated by Mexicans.

We would never argue that things are perfectly fair for the locals — or that wages couldn’t be higher still, and with more job benefits and protections. Also, Indigenous people have mostly been shut out of the prosperity.

But the idea that the area’s bustling economic activity isn’t reaching the local folks is, well, hogwash.

“I’ve traveled to many other parts of [the state of] Guanajuato and Mexico, and many towns and villages have far fewer young men than there should be because so many have moved to the U.S. for jobs,” says one local business owner. “But here in San Miguel de Allende, there are still young men. They’re able to stay because they can find work.”

Sure enough, an incredible 1.2 million people have moved from this Mexican state alone to the U.S. — most of them for better economic opportunities. (The ongoing deportations of immigrants by the Trump administration could have dire consequences in this part of the world.)

But thanks to tourism and foreign immigration, there are now big opportunities for those who stayed — people like Emilio and Karen, the owners of Sucre Bakery.

They opened their business right after COVID, and they’ve since seen rapid growth — so much so that six months ago, they moved to a better location (in the Guadalupe neighborhood near the city center). They’ve now hired three employees, and taken on two interns from the local university that they also plan to hire.

Their bread is absolutely amazing, but let’s be real: it’s not Mexicans who are paying $4.50 USD for one gourmet loaf.

It’s also easy to romanticize San Miguel’s pre-tourism and pre-gentrification past. “You used to see kids walking around with no shoes,” says one older local.

Now it’s common to see kids playing fútbol — or soccer — in one of city’s many playfields.

Poverty is still an issue in San Miguel, and economic inequality is technically larger than ever, thanks to all the wealthy foreigners and also Mexicans from Mexico City — the latter of whom locals sometimes derisively called “chilangos” or even “whitexicans.”

But after several decades of strong growth, the economy is now fairly diverse, and extreme poverty is much less of a problem than in many parts of Mexico. San Miguel has a fairly strong middle class, at least by Mexican standards.

“I think ninety percent of the locals would say that, overall, things are better now,” says one local businesswoman, an immigrant from America. “And ten percent just want to complain.”

In fact, it’s easy to see what San Miguel de Allende would be like without tourism and gentrification: the town of Mineral de Pozos, about 60 kilometers away.

Both San Miguel de Allende and Mineral de Pozos boomed in the 19th century due to the area’s silver and gold mines. But when the mines closed, the local economy crashed. At one point, San Miguel fell from a population of 30,000 to only 8,000.

But San Miguel eventually made an economic shift to manufacturing — which also eventually imploded — and then to tourism, which is now largely responsible for the city’s booming economy.

Mineral de Pozos was unable to adapt, and while the town was once home to 70,000 people, it’s now virtually a ghost town with only 2,000 residents. Tourism is slowly increasing, but frankly, the town would kill for more of the tourism dollars that so many people say are “destroying” San Miguel de Allende.

Still, much of the discussion around San Miguel isn’t about economics — it’s about that ever-popular buzzword, “authenticity.”

“Many of the boutique stores and restaurants seem to cater to the expat/foreign tourist crowd,” writes another foreign observer. “Don’t get me wrong — it’s a beautiful town. But it just didn’t feel ‘as Mexican’ as some of the other towns and cities I’ve visited in Mexico. And that’s what was missing for me. San Miguel de Allende is what I call ‘Mexico-lite.’”

Others say San Miguel has been “Disney-fied” — and in a way, it has been. But that’s partly due to the strict guidelines imposed by the UNESCO World Heritage listing.

And some of the area’s manicured ambiance is because, yes, this is exactly the kind of “charm” that tourists and wealthy foreign immigrants want to see.

Vail Smerlinder-Suarez agrees that from a local point of view, some of the retirees who have immigrated to San Miguel can be trying.

“I’ve had some of these people say to me, proudly, ‘I’ve lived here twenty years, and I don’t know a word of Spanish!’” she says. “I always tell them, ‘Do you want to learn? Because I know people!’ I’m sure these are also the same people who, back in America, say that everyone should learn English.”

But at the same time, the town seems to us to be far more “Mexican” than many critics suggest. There’s been some fantastic festival or event almost every week we’ve been here, with the participants nearly all locals or Mexican tourists.

Also, the influence of all these foreigners on this place hasn’t only been negative.

Elisa Torres, who has lived in San Miguel most of her life, marvels at the cultural changes.

“Growing up, my grandmother told me, ‘Be careful, because foreign people are crazy,’” Torres says. “For us, the foreign women were too much. We would see their kids jumping everywhere, and the [local] women would say, ‘That is not happening in my house!’”

But gradually, local attitudes began to change, especially among women.

“Little girls would go into these houses [of the foreigners], and the foreign women would say, ‘Would you like to read a book?’ The girls would think, ‘One day, I want to be like her. I want to study, I want to open my own business.’ My grandfather would say, ‘No, you are going to work [in the home].’

“But later, my grandmother said, “No, [the girls] need to be free.’ Finally, both my grandmother and grandfather said, ‘We want what’s best for them — the girls can go to school. Because one day they will do something different.’”

Torres is especially grateful that so many foreign residents have integrated themselves into the community, opening businesses and creating jobs, yes, but also offering an almost endless number of classes at the community centers — all for free.

“People come from outside with new ideas,” she says. “And now we have access to different things that you never dreamed of in your life. It’s amazing, actually.”

And Smerlinder-Suarez points out something more practical, if very depressing: “When the gringos move into your neighborhood, yes, prices go up. But the government also notices, and they pave the street. They suddenly care about all the things you’ve been complaining about.”

One Mexican business owner agreed, telling us, “San Miguel has better sanitation, education, and safety than all the neighboring towns — because of the presence of foreigners.”

The issues of “tourism” and “gentrification” are complicated. The world is an unfair place, and international tourism and immigration from wealthier countries have real-world consequences — with clear winners and losers.

Also, things change. When something is gained, something is always lost.

But Mexicans are well aware of these trade-offs, and they’re flocking to San Miguel anyway.

And so, the more the two of us travel — and the more locals we talk to — the more we think…

Well, maybe these issues aren’t that complicated, at least not in San Miguel de Allende.

Ultimately, the most important question is: Is life better now for more local people than before?

Here, it seems to us that the answer is a pretty clear yes.

See our companion piece: Has Tourism Been Good or Bad for the World?

We recommend Vail Smerlinder-Suarez’s local food tours at Taste of San Miguel. She has tours for families too: Turistando en Familia.

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author. Check out my new newsletter about my books and movies at BrentHartinger.com.

Michael Jensen is a novelist and editor. For a newsletter with more of my photos, visit me at www.MichaelJensen.com.

For myself, I grew up in an U.S. Army family, and we spent seven years in what was then called "West" Germany. Even though we lived in Army housing, went to Army dependent schools, and shopped at the Commissary and PX, we also shopped and ate meals "on the economy" (in German stores), and when in Frankfurt, rode the "Strass" (short for "Strassenbahn", or streetcars) around the city, and when I was old enough to date took them on day trips up the Rhine River.

I feel those years in another country, on another continent, made me into a more worldly, tolerant, and accepting person than I would have been if my family had stayed in a small town on the South Dakota/Minnesota border surrounded by largely people I was related to by blood or marriage, or even lived in San Diego where Mom was from.

I don't know how "good" that was for the German people, though having American money flooding in from the military, as well as from civilians traveling, shopping, and eating out on the economy certainly didn't hurt Germany's recovery after WWII.

Excellent! I was reluctant to go to San Miguel Allende - hearing that it was just full of gringos. But I'm glad we went. Although I heard so much English there, I was surprised to see so many Mexican tourists. I love being around Mexican tourist, they know how to have fun!

We have Mexican friends who have a second home there. They are retired school teachers - so not your typical rich people from Mexico City. They love the city. I enjoy seeing there post of where they go and what they do. I think they also enjoy hanging with all their gringo friends there.

I happy to hear that the influx of foreigners has been good for San Miguel. It is really a stunning city.