The Surprising Thing I Discovered Inside an Istanbul Hammam

Hammam bathhouses are an essential part of Turkish culture. But something I found inside made me reassess myself.

Coming to Istanbul, we knew we wanted to visit a hammam. Personal cleanliness is an important part of Turkey’s Islamic culture, and the country’s famous hammams are one of the ways these Muslims traditionally stay clean.

But when we told our neighbor Duman about our plans, he said, “No. You must not go to one of the tourist hammams. You must come with me to my hammam. No tourists ever go there.”

Naturally, we were intrigued, even before he added, “You know what the tourist hammams charge? Five hundred lira. My hammam? One hundred lira. And the massage is longer too. Not just get you in and out for another customer.”

That was about eleven US dollars versus sixty.

So a week or so later, Michael, Duman, and I — along with Duman’s friends, Artemis and Yusuf — piled into the zip-car Yusuf had rented for the night.

And we drove. Like, an hour. Which isn’t necessarily saying we drove far, because traffic in Istanbul is horrendous. But this place wasn’t on a metro line, and there would have been a lot of bus transfers to get there. Besides, a zip-car for the whole night cost all of thirty-five lira — about four dollars.

Still, we drove for a long time outside Istanbul’s majestic if crumbling city walls, and at one point, I thought, “Should I be worried? A month ago, I didn’t know any of these people.”

Except I wasn’t worried, not at all. I didn’t know Yusuf or Artemis well — and, in fact, neither of them spoke English. But I’d had many lovely chats with Duman, and I trusted him completely. If this was a con, it was the best one in history.

Finally, we passed through one of the openings in the ancient city walls and arrived at the hammam. Duman told us the building was nine hundred years old, though, in fairness, the sign said it had only been a hammam since 1489.

We went to our individual dressing rooms, where I stripped naked and wrapped myself in the peştemal, or hammam towel.

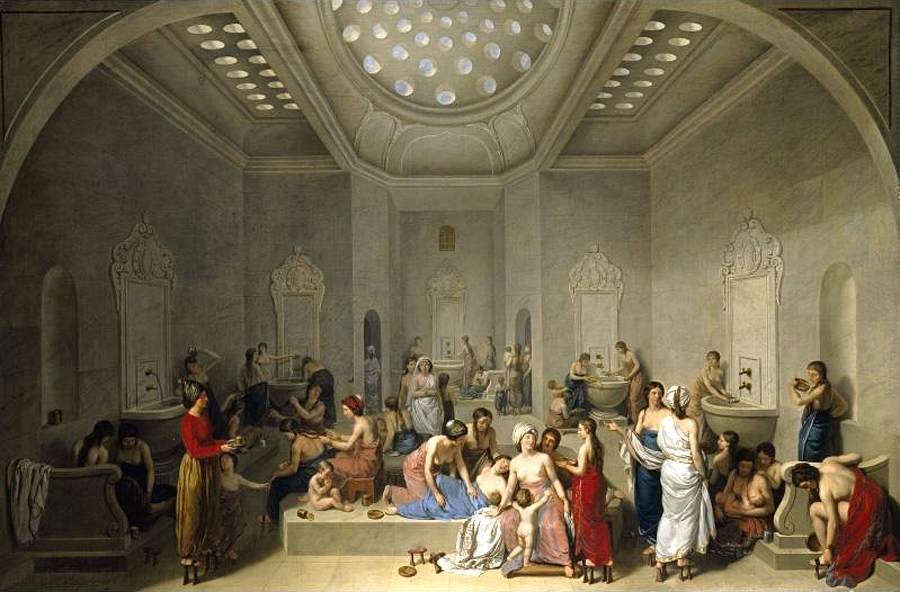

Duman led us to the hot room, which is a large domed room with water basins all around. By now, we were segregated by sex, but Duman, Yusuf, Michael, and I climbed up onto the göbek taşı — a large marble platform under the dome.

“It’s heated by real burning wood underneath!” said Duman, excited. It definitely felt like it. “The heat and sweat will push the dirt out of your skin.”

As we lounged, chatted, and began to sweat, the attendant brought us large glasses of freshly squeezed orange and lemon juice, and a large tray of chilled, sliced watermelon.

When we were all thoroughly drenched with sweat, the masseur, called a natir, appeared. I went first, and he led me into the tepid room, which is like a steam room, where my entire body was scrubbed with a kese — a rough mitten — to get the dead skin cells off.

And very private parts aside, I do mean my entire body.

Then I was washed and rinsed in warm water from nearby basins, and the natir clipped my toenails, which I definitely didn’t expect.

Next came the köpük, which is the famous soap massage. Your body is engulfed in great mounds of very warm soap bubbles, and then you’re massaged. And again, except for my very private parts, I was massaged all over, and for a very long time.

My body was kneaded, folded, twisted, and pounded. I later learned that my natir apparently practiced a form of chiropractic massage that Michael’s didn’t, and I wasn’t always a fan.

There was also a breathing ritual where the natir and I briefly breathe the same air, and I didn’t love this either, at least in the age of Covid. But hey, I’m vaccinated.

All through this whole ritual, I did everything wrong. I sat on my stomach when I was supposed to be on my back. I sat up when I was supposed to lean back. I opened my eyes in the middle of the soap massage.

I really regret the last mistake, because while those warm bubbles feel amazing, they’re not made with Johnson’s Baby Shampoo, so they stung like hell.

Still, through it all, I was never embarrassed, not even a little, because, hey, it was my first time in a hammam, and how the hell was I supposed to know what to do? The natir didn’t speak English, but he always patiently smiled at me, directing me what to do next.

Even the nudity felt like no big deal, perfectly natural in the context of the place. People had been doing this for thousands of years — for half a millennium, inside this very building. Did I really think there was anything these walls hadn’t seen?

I finally had one more rinse with warm water, and I was led into the cool room, where another attendant gently dried me, even fanning me in various in places.

Then, wrapped in towel, we all gathered for Turkish coffee and another casual chat.

The price for all this food and drink, and the “complete” service experience? Three hundred lira for both Michael and me, about thirty-six US dollars — though we gave another hundred lira tip, which, based on the reaction of the workers, might be the largest tip ever given at this place since it opened in 1489.

Later, back in our home neighborhood, we took Duman and others out for ice cream and talked some more. Four out of five of us didn’t speak the same language, but by now, I was used to Duman translating for us.

At one point, Artemis said something in Turkish, and Duman laughed, and I said, “What did she say? What did she say?”

“She said, ‘Everything in life is a lie, only the hammam massage is true.’”

And I laughed too but also nodded, because I actually thought what she said was very profound.

Later, when it was almost time to go home, I said to Duman, “Thanks for tonight. It was really fun.”

He looked at Michael and me for a moment, thinking. Then he said, “You are American, but you are not like Americans. You do not act like tourists.”

I knew part of this was just Duman sucking up to us, because, come on, that’s what good friends do: they tell us what we most want to hear, right?

But he seemed sincere, and I was curious what he meant, so I said, “What do you mean?”

“You do new things, but you are comfortable,” he said. “You are not nervous or uptight.”

But I am! I immediately thought. I’m sooooooo uptight! How in the world could you have such a wrong impression of me? I’m not a risk-taker! I’m not an adventurer at all!

Except I’d moved to Istanbul a month earlier, and met some random Turkish friends, and let them drive me far out into the city, so I could strip naked, and have my body soaped up and twisted and breathed on, deep in the bowels of some ancient, forgotten building.

And it hadn’t been any big deal. Like, at all. It was literally just another day in the life of Brent and Michael.

So was I not the same person I’d been when I left America four years ago? Did Duman know me better than I knew myself?

Except here’s the thing: I haven’t really changed. I still am the same person I was before! I’m not a risk-taker, and I’m not particularly adventurous.

I’ve just learned the vast majority of the world isn’t anything to be afraid of.

This was the “shocking” thing I saw inside that Turkish hammam: I’d learned yet again that most of my former fears about the world were completely unfounded.

I mean, you can’t be an idiot. You always have to do your due diligence, and trust your instincts, and have the confidence to speak up if something feels wrong. And, of course, you should never take unnecessary, stupid risks.

But if you follow these rules? You’ll most likely be just fine.

Here’s where I openly concede that much of the comfort I now feel in the world is the direct result of the privilege that comes from being a white American male with money — not a lot of money, but some. A lot more than most Turkish people.

But remember what Artemis said about how the hammam massage is the truth and the rest of life is the lie?

That’s true of fear too, at least for middle class Americans like me. Most of what we fear — not all, but most — is the lie. The truth is the joy we feel when we refuse to give into our irrational fears.

I recently wrote about foreign toilets, how they sometimes seem weird and “scary” in YouTube videos.

But when you’re actually there, when you see things in context, they don’t seem weird at all. On the contrary, if you’re willing to make a small mental leap, they seem perfectly normal. Because they absolutely are!

All over the world, most things are normal. Just because they’re unfamiliar, that doesn’t mean they’re dangerous.

On the contrary, the diversity of the world is exactly what makes it so interesting. And beautiful.

And now I am determined to see as much of it as possible before I die.

If it’s an option for you, I hope you get to explore the world too.

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author, and one half of a couple of traveling gay digital nomads. Visit us at BrentAndMichaelAreGoingPlaces.com, or on Instagram or Twitter.

I fondly remember my hammam visit in Bodrum 30 years ago at the Princess Karia Hotel. Other than the man massaging me, who grabbed my breasts then said “you like”? 😂

Fascinating glimpse into a part of Turkish culture that few outsiders get to experience! I’ve never been to a hammam but I’ve been to a Korean sauna for a body scrub which seems to be a similar experience, except my private parts were washed along with everything else! It was very businesslike and professional. Unexpected, but I didn’t mind it at all. 😊