Istanbul's History is Long, Amazing...and Perhaps a Little Bit Smothering.

Plus, sometimes "elegant decay" just means "run-down." And don't get me started on graffiti!

Brent and I come from Seattle, a city founded in 1851. Or about, oh, 2500 years after Greek settlers first colonized what is today’s Istanbul, where we’re now living.

The oldest existing structure in Seattle is a house that dates from, uh, 1852. Calling that “old” is laughable to someone from Istanbul. Hell, that’s practically a toddler here.

In fact, just down the street from where we live is Galata Tower, which was built in 1348…on the site of a previous structure built 800 years before that.

Every time we step outside our apartment, we’re confronted by some ancient marvel or monument commemorating Turkey’s former glory as both the Byzantine Empire, which lasted a thousand years, and the Ottoman Empire, which lasted another six hundred years. Both empires were massive, spanning three continents and controlling much of the “civilized” world.

So, yes, I’m constantly astonished by all the mosques, monuments, squares, and structures. Half the time my mouth must hang open like a trout that’s just been whacked on the head by a fisherman.

But that has me wondering what it must be like to be Turkish and living surrounded by so much ancient history. Especially in a city that used to literally be the crossroads of the world, and is now, well, still a massive, important, and extremely interesting metropolis, but not nearly as important as it once was.

Is that history inspiring for Turks, or smothering?

Does all this distant, glorious past make a person feel like anything is possible? Or that living up to that past is impossible so why even try?

We asked our Turkish friend, Duman, but he didn’t really understand the question. Frankly, for locals like him, this is an unforgiving city with a repressive government, and Duman is too busy simply trying to survive.

Which is kind of an answer in itself. Istanbul, once a seat of great learning, is no longer a place for much navel-gazing.

“Turks are too busy worrying about today to think about our past unless we go to a museum,” Hosmunt, a barista at my local coffee shop, told me.

Cetin, a nearby café owner, agreed that most Turks don’t really think about their past. “They have no respect for their history. They don’t care. They see a five hundred year old building and just spray their name on it.”

I would never say that a people or a city are “broken,” but there is definitely a sense that the Istanbullar are weary. I think that has to do with the current world order and, yes, their long and storied history.

Brent and I had similar thoughts about the weight of history when we lived in Italy, another country with a long and incredible past.

I asked Susanna, an old Italian friend, for her thoughts, and she said, “We have a saying in Italy: ‘We are living with the rent.’ Which means you don't really put in any effort in creating a new business or whatever. You are just living with what you get from the past. I don't think we are inspired by the past. The common people like me are fascinated by history and think it is beautiful and something to be taken care of. But I have never been inspired by it.”

I’m not too surprised that my reaction to these two countries is so different than that of the local Turks and Italians. When human beings travel, we often go in search of the unfamiliar, things we haven’t seen before.

Meanwhile, where we actually live is often commonplace — and, therefore, uninspiring — to us.

Brent and I look at Istanbul and Italy and see nothing but history in every direction, Turks and Italians just see the place they’ve always lived.

Which makes me wonder what obvious things I took for granted about the place we left.

We’re currently living in the neighborhood of Beyoglu, which is the part of town that gained Istanbul the nickname “the Paris of the East.” This part of town rose to prominence in the mid-1800s and, in fact, was built using French architectural styles.

But time, and gravity, never stop their endless pull, so you also have signs of age and deterioration. Turkey is a now relatively poor country that can’t afford expensive upkeep.

Sometimes that decay can be quite beautiful. “Elegant decay” is the idea that cities and buildings become even more beautiful as they fall into ruin. The age and history of a place becomes part of the design.

The most famous example is probably New Orleans, with its crumbling French Quarter, and also the Garden District, where Spanish Moss and the heat and humidity slowly take their toll on the cemeteries, the crypts and headstones crumbling, the graves being swallowed by the sinking land.

Venice, too, might be even more beautiful now that its palazzos are slowly crumbling, and the stones in the steps and piazzas become ever more rounded and polished as more people walk over them.

Some parts of Istanbul are also defined by elegant decay.

But maybe sometimes decay is just decay.

Sometimes it can be hard to decide the difference between the two. One person’s elegant decay might very well be someone else’s obvious eyesore.

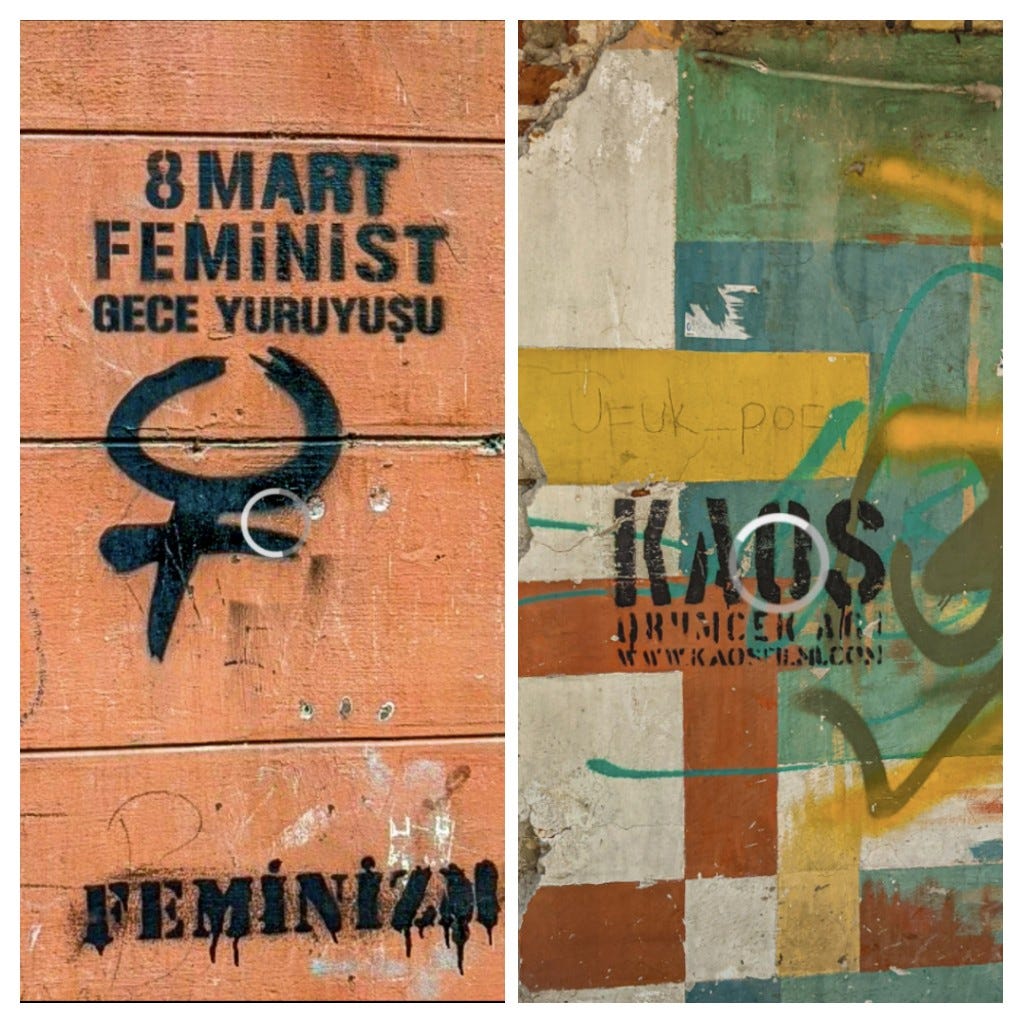

Speaking of attractive, or not, what’s the difference between street art, murals, and plain old graffiti?

Like “elegant decay” and “ugly eyesore,” the difference is often in the eye of the beholder. Let me add that I’m well aware that everything that follows is just my opinion. But this is my column, so there!

There is some beautiful murals and street art in this part of Istanbul, but there is even more graffiti — and like Cetin (the café owner I quoted above), I don’t like it.

But trying to keep an open mind, I did a little research into the differences between street art, murals, and graffiti.

Let’s say those categories are all a bit murky and there is a lot of overlap. It goes back to the whole “eye of the beholder” thing.

Murals are paintings on walls, sides of building, etc. with the permission of the owner or local authorities. They are also signed by the artist and often incorporate parts of the structure like doorways and windows.

Street art resembles murals, but is usually done without permission, though it sometimes is. It’s also sometimes signed by the artist and often, but not always, makes a political or social statement.

I told you this was all very murky!

Graffiti is where things become truly confusing. Suffice to say there are a lot of different opinions on graffiti — and its artistic value.

Graffiti is almost always done with spray cans or markers and is usually signed with a “tag” that is not the artists real name. Graffiti artists usually don’t care what anyone thinks of their work — except other artists. Often times the meaning of the art — when there is meaning and isn’t just plain old vandalism — is unclear to the general public. Usually purposefully so.

Personally, I love murals and street art. And I will admit that sometimes graffiti can be striking and political and important.

But I think the value of some graffiti is way way outweighed by the fact that so much of it is juvenile crap done by bored teenagers that damages the property of people who have done nothing to deserve it.

Can you tell I’m writing this as a former property owner?

Brent and I had a beautiful red cedar fence in our house back in Seattle that was spray painted with graffiti. Graffiti that permanently damaged the fence because the only way to get rid of the it was to paint over the fence.

I’d have happily taken a can of spray point and visited the “artist” and expressed my feelings all over their personal belongings.

Here in Istanbul, I’ve seen graffiti defacing entire streets of businesses, all over ancient doorways and walls, even pieces of actual art, like public sculptures.

Sure, maybe sometimes it’s the voice of the oppressed. I still think it’s a shitty thing to do to a business owner struggling to make a buck. Or a Turkish lira, as the case may be.

That being said, there are abandoned sections of town and long stretches of concrete walls alongside busy roads here in Istanbul that are covered with graffiti — and they are admittedly pretty interesting.

And they would probably be even more interesting if I understood the meaning and symbolism involved. But since most graffiti artists aren’t doing their “art” for the public but only for themselves and other graffiti artists, I guess that won’t be happening.

That’s it for this week, but before I go I have a request.

Actually, this totes adorable stray kitty here in Istanbul has a request. He really enjoys our newsletter but knows that in order for us to succeed as travel writers we need to grow our audience.

So if you’ve enjoyed reading about our travels, we would truly appreciate it if you helped spread the word. Maybe forward this column to a friend you think might be interested.

Or share the word on social media. Any little bit would be greatly appreciated by this sweet sweet kitty.

And, of course, us as well.

Goodbye until our next hello!

Michael (and Brent)

Michael, check out the restaurant Albura Kathisma. Besides good food, they found an old "palace" from Roman times underneath the resto. It is being excavated over time. They will let you in if you ask. One of the coolest things we saw in Istanbul!

Great post. Same here in Portugal, at least in Lisbon and Sintra. If the locals simply think that that their architecture is simply something beautiful to be protected, that's good enough. Americans wouldn't even go that far.