Is the Islamic Call to Prayer a Beautiful Ritual That Binds Communities Together? Or an Intrusive Relic of the Past?

It depends on your point of view.

For the audio version of this article, read by the author, go here.

Let’s get one thing straight: whenever I visit a foreign county, I am a visitor — a guest in someone else’s home.

So I’m always very respectful of local traditions like, say, the Call to Prayer in Muslim countries.

This is the ancient Islamic tradition of calling out a prayer or song to announce to the community that it’s time for one of the day’s five daily prayers.

Praying regularly is one of the “Five Pillars” of Islam (or the “Ancillaries of the Faith” for Shia Muslims), and the Call to Prayer is usually “called” from the top of a minaret — a type of religious tower — attached to the local mosque.

Turkey, where Michael and I are now living, has its own system of music called makem, which is incredibly complicated, completely unlike Western melodies.

As such, in Turkey — and only in Turkey — the Islamic Call to Prayer is expressed in five different ways, each “song” depending on the time of day.

Unfortunately, one of those songs comes very early in the morning — technically, between the break of dawn and sunrise.

And since we’re staying in the Balat neighborhood of Istanbul, on the top of a steep hill, we can hear the Call to Prayer from mosques down below us all over the city.

It’s actually quite haunting and spectacular: waves of wailing voices blending together, rising and falling in a kind of a ghostly chorus.

Michael recorded it one morning:

It was fantastic to hear the first morning after we arrived.

It’s been less fantastic having it wake me up almost every morning since then. Sometimes I can fall back to sleep, but sometimes I can’t, making for a miserable, cranky day.

And on my worst mornings, I forget that belief of mine about being a guest in foreign countries, and a petty part of me thinks, This is rude. I get it, it’s an important religious tradition. But I’m not Muslim. Why are you forcing me to participate in your tradition — especially in the middle of the night?

In fact, when looking for lodging in Muslim countries, Michael and I now usually inquire about the local mosques — and try to stay as far away from them as possible. But in Istanbul, home to sixteen zillion mosques, that’s essentially impossible.

The very worst was when we lived on Koh Lanta, a minority-Muslim island in southern Thailand. Our bamboo bungalow on the beach was the perfect expat fantasy — except for the fact that early each morning, the mosque next door sounded like howling cats mating right behind our headboard.

Mine, of course, is a very “American” point of view. Turkey is 99.8% Muslim, but America is much more diverse, with lots of different cultures and religions who all have to somehow live together. As such, most practicing American Muslims keep track of their daily prayers themselves, even using “Call to Prayer” apps on their phones.

But interestingly, some American communities are now making exceptions to their noise ordinances to allow the Call to Prayer from local mosques (albeit without the early morning and late evening calls).

And, of course, it must be said that Christian church bells, which are an accepted part of many communities, are also a call to prayer — even in Europe where Islamic Calls to Prayer have been very controversial.

In America, we’re very big on the individual, and also individual rights. But is changing local laws to allow the broadcasts of the Islamic Call to Prayer the “free exercise” of religion — or a “government endorsement” of it?

It’s a bit complicated, isn’t it? Two important rights are in conflict. After all, your right to swing your fist ends at my nose.

Does your right to broadcast music end at my eardrums?

And “broadcast” is sometimes a key question: if mosques do a call to prayer, do they really have to amplify it over loudspeakers? How is that traditional? In 2021, even Saudi Arabia told its mosques to, well, pump down the volume.

Then again, times change, and sometimes traditions change with them.

It’s also worth pointing out that Turkey’s “99.8% Muslim” figure? That’s the official count. I now have many Muslim friends in many Muslim countries, including Turkey, and many tell me they’re not observant Muslims. Some are even atheists.

Then again, some of these same friends tell me that Islam often isn’t really a religious choice so much as a cultural — and even racial — identity. You can’t opt out.

In many countries, Muslims are even subject to Sharia, or Islamic, Law. And the legal system often enforces that law, including with penalties.

Malaysia, where we lived last year, has two parallel legal systems: one for Muslims, which make up 64% of the population, and one for everyone else. If you’re born Muslim, you’re bound by these separate laws whether you want to be or not.

Muslims enforce these laws too, both formally and informally. The McDonald’s across the street from our apartment in Penang had a sign reminding patrons that Muslims were not allowed to eat during daylight hours during Ramadan. And a local Muslim friend told us that, yes, that ban is absolutely enforced by the employees there.

People spy on — and turn in — their neighbors too.

And this particular article isn’t the place to open the enormous can of worms that is the question of how many Muslims — and mosques — treat women and LGBTQ people.

The greater point is, my Muslim friends don’t necessarily want to be woken up at five in the morning either.

Although I think some of them would also be quick to point out that, in many ways, Islam is an amazing religion.

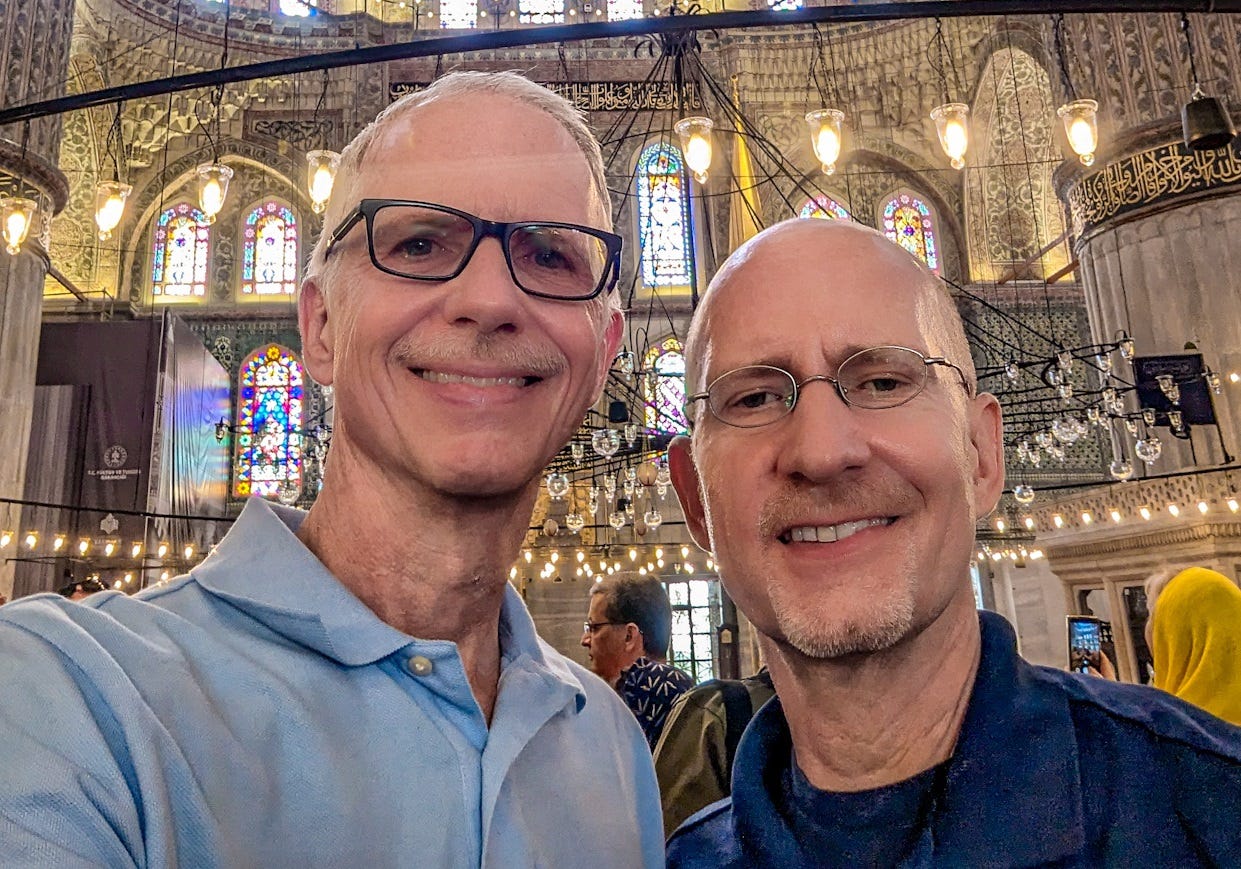

Once when Michael and I were visiting a mosque, below, a young woman explained to us the importance of the various rows of stained-glass windows.

The bottom row of windows, clear and bright, represents the purity of the child.

The next row up, with its bright colors and focus, represents young adulthood with all its clear-eyed certainty.

But by the next row, representing adulthood, the clarity has given way to more muted colors, and the blurry acknowledgement of the complexity of life.

In the fourth row, representing old age, the world grows more muted, infused with wisdom but also fading life.

Finally, the last row represents death, and the dazzling clarity that comes with eternal enlightenment.

I’d like to think that even the world’s worst Islamophobe would be moved by the profound beauty of these windows, which are found in many mosques.

And I think the idea behind the Call to Prayer is quite profound too: something outside yourself that the entire community shares, giving it focus and binding it together. In many Muslim communities, the Call to Prayer is so important that they make it the first thing a newborn baby hears.

Mosques are about the community too: a gathering spot and a place of support for the old, the disabled, and the poor. In Turkey, mosques also support the many impoverished refugees from places like Syria and Afghanistan.

I was raised very Catholic, and there are many things I hated about my childhood, which was often prosaic and stifling.

But these days, I often think: Even my dreary childhood Catholicism is better than the prevailing attitudes in America these days. It’s all about consumerism!

And don't get me started on social media, which seems increasingly toxic. Was everyone always so self-centered?

Which brings up one of the great ironies of my traveling the world for the last seven years: I’ve started seeing the flaws of my own culture much more clearly than before.

And I’ve also realized that other cultures aren’t different from mine because they’re silly, or weird, or stupid.

They’re different because, in many ways, they work — at least as well as America does.

Which, of course, is worth remembering the next time the Call to Prayer wakes me up at five in the morning.

Brent Hartinger is a screenwriter and author. Check out my new newsletter about my books and movies at www.BrentHartinger.com.

Friends in England lived in a village, next to a church where the bells chimed the time, even on the quarter hour. I quickly got used to it when I stayed in the 90s, and was sorry to hear that the rich newcomers of recent years had demanded it be curtailed. I also grew up under a flight path, have stayed with family who lived next to railway lines, and now live close to a freeway. I know which sound I prefer to be burdened with.

Learned something new about the stained glass windows in Turkey Brent! As a Muslim American, I hear you on the question of why the athdan needs to play for each prayer. I’ve been to Turkey and Malaysia too, and found the sounds beautiful but then I return to the suburbs here and there’s no sounds at all, even though there’s a mosque down the street. For Muslims, the call to prayer is like a reminder, a visceral reminder, “come to prayer, come to success.” The translation of the Arabic is interesting to me as a non-native speaker. I think it’s saying there’s something more than this world… but I can imagine how annoying the call could be if you just need to sleep. There’s actually noise pollution all around us, every time we go to a store, a cafe, anywhere, but the athan is also over in less than 5 minutes which I like too. I loved hearing church bells as a kid but I never hear them anymore.