Do "Immersive Experiences" Expand Our Minds? Or Cut Us Off From Reality?

"Immersive entertainment" like Meow Wolf and Wake the Tiger are sweeping the world. Is this a good thing?

Five glowing mushrooms rose from a fluorescent rock while colorful tendrils radiated outward across the ground. Massive roots climbed up the walls behind.

It was a fantastic sight — in a place filled with fantastic sights.

Brent and I had come to Wake the Tiger, a walk-through attraction in Bristol, England, that bills itself as the world’s first “amazement park.” This was just one of dozens of decorated spaces, each more spectacular than the last.

The experience tells a story of sorts.

You begin in what is supposedly an abandoned paint factory — a place that one day saw the appearance of strange, otherworldly mushrooms.

These mushrooms have somehow opened a portal to another world: a dystopian place called Meridia. As you explore this strange new realm, you encounter a steampunk library with a tunnel of infinite books, a raging fire you can touch, and, yes, lots more mushrooms.

Clever observers will discover clues that reveal that the former residents of Meridia have combined the elements of air, fire, water, and earth with these strange mushrooms to transport themselves to a place beyond reality, the OUTERverse.

Eventually, you go there too — right before you exit into the gift shop.

Wake the Tiger may call itself the world’s first amazement park, but it’s really just the latest in a long history of such “immersive entertainment.”

It’s different from a book or theater experience because it’s more interactive. You’re literally in the story. You participate, at least a little.

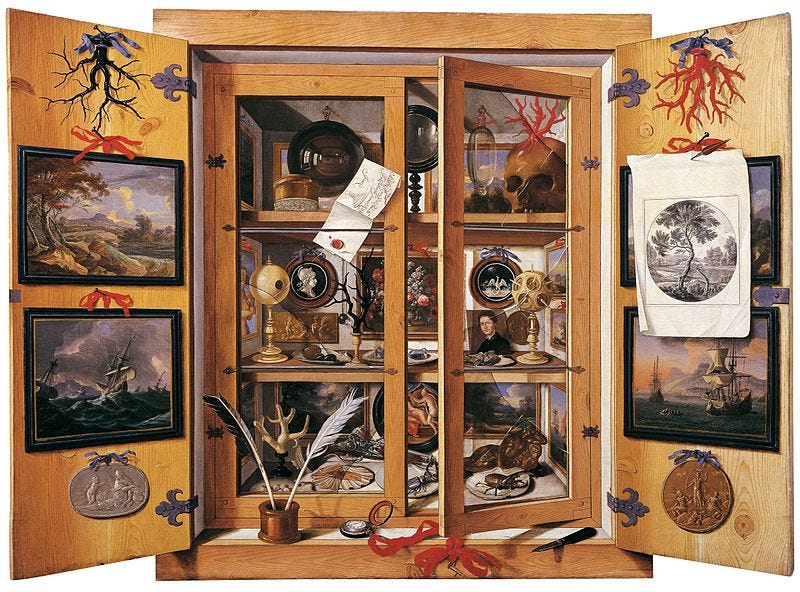

The first modern immersive experiences may have been the “cabinets of curiosities” that first appeared in 16th-century Europe. These were collections of strange and unusual items displayed by their owners, usually wealthy European aristocrats.

Sometimes these were actual cabinets.

At the same time, a “cabinet” once referred to a whole room filled with novel items. These were also referred to as wonder rooms.

Collections included mounted insects, stuffed birds, mammals, and reptiles — often “exotic” examples from far-off lands. Also popular were stuffed “freaks of nature”: two-headed cats or snakes and the like.

Some owners even created or commissioned fantastical creatures such as basilisks and dragons fashioned by piecing together various real-world animals.

But almost anything could end up in cabinets of curiosities: antique brushes, African necklaces, calligraphy from Asia — whatever struck a collector’s fancy.

Cabinets of curiosities were rarely open to the public, instead providing entertainment for Europe’s wealthy. Entering a wonder room was to immerse yourself in the world’s mysteries.

When the Scientific Revolution swept Europe, cabinets of curiosities were gradually replaced by museums. These were similarly immersive experiences, but the items were grouped more according to scientific principles. The point was also to educate rather than merely impress.

Soon, museums created life-size dioramas with, say, stuffed lions and dried plants — which transported the viewer to the plains of Africa.

The Great Exhibition, which took place in 1851 in the Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park, was a massive leap forward in immersive entertainment.

Part of it was the building itself: the largest glass building ever constructed — by far! — built around three existing massive trees, essentially creating an enormous greenhouse. People had never seen anything like it.

Inside, 15,000 exhibitors displayed some 100,000 items — many with a scientific bent. Visitors could watch steam engines drive pistons, see an early fax machine and the world’s first voting machine, listen to music from foreign instruments, and smell and taste foods they had never encountered.

The Great Exhibition proved so popular that other countries began emulating it, and World Expositions spread worldwide — soon better known as World Fairs.

Different countries began creating other kinds of immersive experiences as well.

In 1891, Sweden opened Skansen, the world’s first open-air museum. Spread over 75 acres, Skansen replicated an entire 19th-century Swedish town. Visitors even interacted with people dressed in period costumes as they engaged in traditional crafts such as baking, silversmithing, and more.

Soon, entrepreneurs got into the game, creating carnivals, freak shows, and “amusement parks,” which evolved from the “pleasure parks” common throughout Europe in the 19th century.

Before long, amusement parks — places like Wurstelprater in Vienna and Coney Island in New York — began to include rides and attractions around specific themes. The premier attraction at Luna Park, which was part of Coney Island, was A Trip to the Moon, which purported to take visitors on an actual trip to the moon — dancing moon-maidens included.

But with Disneyland, which opened in California in 1955, Walt Disney massively reimagined the immersive experience, with entire “lands” filled with different attractions all focused around a single theme.

Before long, art galleries also got into the game, offering more immersive experiences. In the early 1960s, Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama created her first Infinity Mirror Room, in which viewers entered a world that seemed to go on forever.

The exhibit’s success prompted other galleries to create immersive works involving sight, sound, and touch.

Other innovative immersive experiences soon followed.

The first “Renaissance fair” occurred in California in 1963, and similar events appeared across the United States.

In the early 1970s, Griffith Park in Los Angeles debuted “Laserium,” a light show using lasers that transported viewers into entirely imagined worlds built around music. The show was an instant hit, and laser shows were soon to be seen worldwide.

Disney kept expanding, and its new parks and innovations inspired other theme parks around the world.

Then there’s Burning Man, which first burned a wooden sculpture in 1986 and then moved to the Black Rock Desert in Nevada in 1991, where the experience became, uh, bigger.

And if immersive experiences weren’t already immersive enough, the latest examples are being created specifically for social media sharing.

One of the first was the House of Eternal Return, an interactive, permanent art installation that opened in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 2016. Visitors enter a seemingly ordinary house and are transported to alternate dimensions as they explore the rooms. The goal is to solve the mystery of what happened to the family that lived there.

A few months after the House of Eternal Return opened, the Museum of Ice Cream debuted in New York City. It included Instagram-friendly displays that mostly revolved around ice cream.

They now have five locations of what are known as “selfie museums,” including the Happy Place, the Museum of Pizza, and the Museum of Dessert.

Meanwhile, Meow Wolf, the creators of the House of Eternal Return, now have five locations too, all with different themes, including Convergence Station in Denver, which I recently visited with my nephew.

They’ve also inspired imitators like TeamLab in Japan and Wake the Tiger in, yes, Bristol — the place with the glowing mushrooms, where Brent and I were.

These new kinds of immersive experiences have been so successful that ArtNews estimates there are currently nearly 400 found worldwide.

I’m not sure if this number includes the infamous Willy’s Chocolate Experience from earlier this year, which outraged visitors when its dismal reality so dramatically conflicted with its AI-generated advertising.

As for Wake the Tiger — and Convergence Station in Denver — I really wanted to like them both. Futuristic worlds and cool photo opportunities? Those are my jam.

But the “stories” had no stakes and no tension, so I didn’t feel any real emotional connection. They both became boring pretty quickly.

Brent wrote more about Wake the Tiger in his own newsletter, but suffice it to say, we both found it unsatisfying.

But these experiences are definitely visually impressive, which is why the folks walking through the exhibits were taking picture after picture, selfie upon selfie — which, of course, the creators love because it’s free advertising.

This talk of social media brings up the elephant in the room: video games and virtual reality — the ultimate immersive experiences. The video game industry is now larger than the entire worldwide movie and sports industries combined.

Are all these immersive experiences a good thing for society or a bad one?

On one hand, it’s incredible that we’re now able to experience trips to fantastical worlds — just like it was probably a good thing that at least rich folks back in 16th century Europe were able to view items from nature and other cultures in those cabinets of curiosities.

Also, entertainment is ultimately just entertainment.

And if we’re worried about people retreating into cyber-worlds, well, at least these non-virtual immersive experiences are still reality.

Then again, if people are only attending these places to take selfies to post on social media, does that still count as a real-world experience?

Where is all this heading anyway? Most of us already spend too much time looking at screens and living in cyber-realities.

Do we need still more artificial reality?

The TV show Star Trek: The Next Generation predicted that the future might include something called a “holodeck,” an ever-changing room filled with computer-generated holographic imagery. Basically, a person can create any physical reality at all — and live there as long as the power lasts.

But even on Star Trek, things on the holodeck never ended well. Humans have always had a hard time separating fact from fiction — especially when fiction gives them anything they could possibly want.

Then again, almost every advancement in technology and entertainment has been met with cries of doom. Yet here we still are.

The cabinet of curiosities has been opened. For better or for worse, there’s no closing it now.

See also:

London’s Crystal Palace Lives On! (In My Imagination at Least)

Spectacle Without Story is Boring

Michael Jensen is a novelist and editor. For more about Michael, visit him at MichaelJensen.com.

There are some really cool experiences in musems, historic sites, entertainment venues, etc. But I've still never found anything that comes anywhere close to rivaling what nature can do. A mountain, a canyon or a beach are still more spectacular to me.

Here in Kansas City, “Haunted Houses” are a thing every Halloween and have been for decades. They’re easier to stage on limited budgets than the spectacular palaces described here, but limited budgets don’t mean limited creativity, and some can be “immersive experiences” in every sense of the word. All you need is a creepy old house, a bunch of teenagers who aspire to act in horror movies, and a good liability waiver. And a WHOLE BUNCH of fake blood.